News

Kea Aerospace Stratospheric Flight Over Antarctica For Ozone Research

September 26th, 2025

New Zealand government Endeavour project funding has been secured for the Kea Atmos to fly over the Antarctic in the next 3 to 5 years.

Recently, as part of a large research consortium led by the University of Otago, Kea Aerospace was awarded an MBIE Endeavour science grant to bolster understanding of the atmosphere over Antarctica, specifically to develop novel tools to advance understanding and continue monitoring the ozone hole.

The ozone hole has intermittently filled headlines since the 1980s when scientists discovered that ozone, a critical gas in the stratosphere, was being depleted. 90% of ozone resides in the stratosphere, the home of the Kea Atmos.

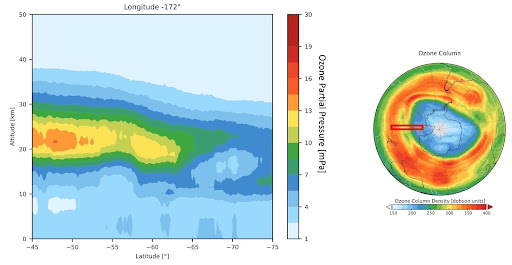

Actually, “hole” is metaphorical—there is no place completely devoid of ozone – a hole is classified when ozone levels fall below the historical threshold of 220 Dobson Units. Dobson Units are essentially a measure of the thickness of the ozone layer as measured by spectrometers on the Earth’s surface. The ozone layer is now also routinely measured by satellites that look down from above and measure the column thickness and distribution of the layer. However, the scientific urgency is growing as a long-term NASA satellite mission monitoring the Antarctic ozone hole is set to end next year — with no replacement on the horizon.

The time series of surface observations starts in 1979, when the minimum was 194 DU, only slightly below the historical low. For a few years minima remained in the 190s, then plunged: 173 DU in 1982, 154 in 1983, 124 in 1985. By 1991, ozone dropped below 100 DU for the first time, and readings under 100 DU became more frequent thereafter. The deepest recorded hole was in 1994, reaching 73 DU on September 30.

Cross-section showing the ozone hole appearing over Antarctica as measured by ESA Sentinel-5P

The ozone layer is absolutely critical for life on Earth. It is a triatomic oxygen molecule (O3). All UVC and most of the UVB radiation is absorbed by the ozone layer, significantly limiting the amount of harmful radiation reaching the Earth’s surface. It is a shield for all living organisms from some of the more energetic, harmful rays the Sun shines on Earth. Without this shield, large doses of harmful radiation would reach the surface, increasing the likelihood of genetic mutations that damage tissues and result in the development of cancers.

The ozone hole formed primarily from human-made chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and similar halogenated compounds released into the atmosphere. CFCs were typically used in refrigeration, aerosols and cleaning products. These stable gases drift into the stratosphere, where ultraviolet light breaks them down, releasing chlorine and bromine atoms. In polar springtime, especially over Antarctica, extremely cold temperatures create polar stratospheric clouds that enable chemical reactions converting these halogen reservoirs into highly reactive forms. When sunlight returns, those reactive chlorine and bromine rapidly destroy ozone molecules in catalytic cycles, producing large seasonal ozone depletion.

The ozone hole is actually an international action success story. The 1987 Montreal Protocol phased out many ozone-depleting substances, which has led to the gradual recovery of the ozone layer.

Large national satellite missions are incredibly expensive and that’s why New Zealand research teams are stepping up, developing a new monitoring system using cubesats at a fraction of the cost of traditional space missions. Kea Aerospace will collaborate with Harald Schwefel and his team at the University of Otago, carrying their miniaturised instruments on stratospheric test flights over New Zealand and Antarctica over the next three to five years. This is a major step forward for both science and stratospheric aviation – and we’re excited to help write the next chapter of ozone research.